Not all forests in Arizona are like the Coconino. Arizona’s diverse geography coupled with enormous elevation changes means the forests are incredibly diverse, Sánchez Meador said.

“Arizona’s forests are arid, high elevation forests which are super dry. They have evolved to be drought tolerant,” he said. “Historically, there was a lot of fire, and so most of our forests, to some degree or another, have some kind of fire adaptation to them, too.”

Arizona goes from high desert – home to saguaros, creosote, mesquite and palo verdes – to woodlands and grasslands in the eastern and western part of the state. Farther north is where the ponderosa pine and mixed conifer forests are, and in some cases, spruce and fir, Sánchez Meador said.

Southern Arizona also has a unique type of forest found on the sky islands near the U.S.-Mexico border.

Elise Sawa, a forester with the Coconino National Forest, explains the difference between a healthy and unhealthy plot of trees to Cronkite News reporters while driving to the next plot near Flagstaff on April 6, 2022. (Photo by Alex Gould/Cronkite News)

“We have all these little cinder cones and uplifted small mountains,” Sánchez Meador said. “As you go up, temperatures get cooler and precipitation falls, and so you get increases in moisture.”

With all this diversity, it can be difficult to define a healthy forest. Sánchez Meador said it comes down to the symptoms a forest shows.

“Our symptoms in Arizona are uncharacteristic fires, which are fires that are burning at high severity,” he said. “When they burn, they destroy forested landscape.”

Other symptoms include tree die-off from drought, fire, insects and disease, which are occurring more often than in the past, Sánchez Meador said.

“I would say those are all symptoms of a chronic problem, which is that our forests in Arizona are largely unhealthy,” he said. “A healthy forest should be able to recover. But our systems are degraded, and they are not recovering. We just aren’t seeing the recovery we would expect to see in a healthy system.”

Why forest health matters: water, wildfire and climate change

The importance of forest health goes far beyond aesthetics and recreation. Forests protect watersheds, which ultimately mean clean drinking water for Arizonans, Sánchez Meador said.

Phoenix, one of the fastest growing cities in the U.S., gets most of its water from the Salt and Verde rivers, as well as from the Colorado River. The headwaters of the Verde are in Yavapai County; the Salt begins in Cochise County.

“Historically, these forests would have been really open,” Sánchez Meador said. “Snow would have melted and gone into the groundwater. But because our forests are so thick today, snow evaporates back into the atmosphere, or runs off. And it never actually makes it back into our groundwater because our forests are degraded and they are not functioning the way we would want them to.”

Aly McAlexander, a forest health specialist with the Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management, sees this degradation first hand.

McAlexander is out in the woods two to three times a week, looking for the impacts of disease and drought, speaking with homeowners about trees on their properties or helping the department survey the forests from a small plane.

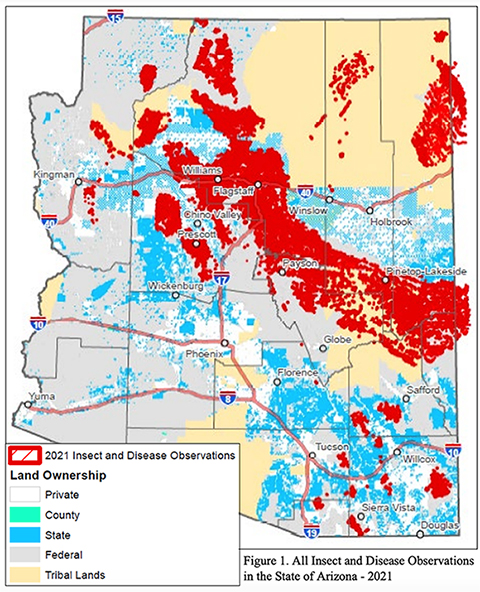

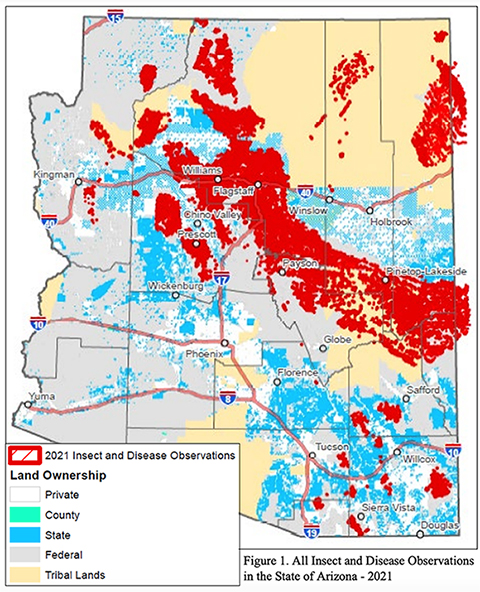

This map shows all the insect infestations and disease outbreaks observed in Arizona’s forests last year. It comes from the Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management’s “Forest Health Conditions – 2021” report. (Graphic credit of Aly McAlexander/ Department of Forestry and Fire Management)

The department surveys the national forests, state lands and tribal lands around Arizona – over 17 million acres in total – during a six to eight week period during the summer, McAlexander said.

“We are looking for insect and disease outbreaks that are occurring that year so we can give a better overall view of what is really happening in all of Arizona,” she said. They go back and ground check some spots if they can’t identify them from the air.

The findings from the 2021 aerial survey indicated that more than 400,000 acres of state land had observable drought damage and 500,000 acres were damaged by bark beetle infestations.

This aerial survey usually is taken once a year, said McAlexander, who has been keeping an eye on Arizona’s forests for two years. But last year, the department conducted a rare supplemental survey to gauge how drought has affected juniper trees.

“We were seeing a large acreage of juniper tree die-off in northern Arizona and a little west of Sedona. We are talking about thousands of acres,” she said.

The impact of drought is obvious, she said.

“We’ve seen the trees begin to have this dingy kind of graying or browning color, depending on the species. There’s an overall stress,” McAlexander said.

Wildfire likes dry, densely packed stands, she said, and Arizona has a lot of those right now.

“With the drought stress going on, trees’ needles are drier because of that lack of moisture, and they’re also fairly densely packed, and this can make them easier to ignite,” she said. “Those things can lead to high intensity fires.”

On top of that, unhealthy trees aren’t as productive, McAlexander said.

“When we have these stressed trees, they’re more focused on trying to maintain their own health, so they’re not able to produce as much oxygen or take in as much carbon dioxide,” she said. “The healthier the stand, the more benefits it provides.”

Carbon dioxide is a major contributor to climate change, which is deepening drought and raising temperatures across the Southwest.

Creating resilient forests

When it comes to climate change, McAlexander said, restoring forest health is a race against time. But making a forest resilient takes decades.

“Trees need time to grow,” she said. “Any changes that we’re expecting to see, whether that’s tree planting or restoration projects, are going to take time for the forests to be able to reach a more mature state.”

In Arizona, much is being done to restore forests to health. Thinning and prescribed burning are the most effective prescriptions for a sick forest, experts say.

Thinning, or the cutting of specific trees, reduces tree stand density, which allows other trees to get water and sunshine to grow. This strategy, McAlexander said, is critical to fire prevention.

According to the Forest Service, “overgrown forests are one of the key contributing factors to the current wildfire crisis in the West,” and “science shows that thinning and fuels treatments work.”